Rwanda’s Lesson for America

Rwanda demonstrates how leadership can channel a group’s character toward progress or destruction.

The highest-octane fuel on Earth is a shared purpose between individuals. Civilization’s steps forward and backwards can be traced to people bound together to change their world. It has propelled explorers into outer space and it has buried neighbors under own cruelty.

This double-edged sword defines Rwanda’s narrative, where my wife and I have spent considerable time, and the moral of its story deserves attention as we decide upon who will be the next US President. Rwanda’s success toward becoming the model 21st century African nation is drawn from the same well that propelled the country’s near-suicide in 1994. So what’s the difference? Leadership.

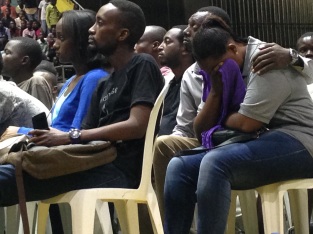

Rwandan society inculcates a view that individuals find safety inside the group. This manifests through subtle and overt social norms: students are less likely to ask questions or make points in class (girls especially), community-wide functions are widely held and attended, and Rwandans are generally receptive to top-down leadership. Umuganda, a modern iteration of an ancient tradition of monthly community service, is universally attended, not just because no-shows are fined, but because deferring to the community is a deeply seeded value within Rwandan psychology.

Conversations we had while working at Agahozo Shalom Youth Village and Akilah Institute for Women in Kigali further revealed popular devotion to community. These teens and students aspire to succeed financially, not to amass personal wealth, but to create jobs for their family and neighbors; their altruism is refreshing, if not startling. It is the engine for a remarkably efficient government initiative to push Rwanda into the 21st century. President Paul Kagame is transforming its capital, Kigali, from a dusty third-world ghost town into a modern center of commerce with new roads, hotels, restaurants, public Wi-Fi, and a brand new, state-of-the-art convention center, as well as a streamlined process to start a business. Rwanda is a developing nation in the truest sense of the term and its leaders push the country towards bolder and more ambitious achievements every day.

But one needs only recall 1994 to understand how dark this type of collective mobilization can turn. Of the myriad factors underlying the genocide, leadership stands at the center. Since Belgian colonizers showed up 90 years earlier, Rwandan leaders trained their people to view all issues through the tribal, zero-sum lens: “Is this good for Hutus or is this good for Tutsis?”. As Rwanda’s corrupt government officials felt power slip through their fingers in the early 1990’s, they doubled down on their only tactic: divide and conquer. That culminated with an unprecedented, vigilante-styled slaughter of a million innocents, committed by the victims’ countrymen, neighbors and even family members, who mercilessly carried out their leaders’ will.

This should be ice water in the face of those Americans whose pessimism clouds their view of the choice in this election. Beyond the enormous policy gulf, there is a canyon separating their demeanor and their driving message. Let’s put aside all the ways Trump personally disqualifies himself from the Presidency on an almost daily basis: He is a sexual assaulter (criminally so), he touts his ignorance, rudeness and cruelty as virtues, and his financial successes have hinged on exploiting the tax code, maliciously manipulating our legal system, and preying on smaller, vulnerable businesses. His moral bankruptcy seems to know no limits or shame, so what sustains his campaign? Sadly, his message, which is: “Things are the worse than ever! And you know whose fault it is? The politicians, the media and the PC losers! Instead of helping you, they’d rather lend a hand to illegal Mexican immigrants and Muslim refugees, some of whom are terrorists(!), while shipping your jobs to Mexico and China!”

Juxtaposed his message with what is Hillary’s angle, which is: “It’s been tough, but even if you can’t feel it, things are getting better. If we keep making incremental changes and use our growing diversity to our advantage, eventually we will all feel the improvements.”

Say what you will about Hillary, her authenticity, and secretive tendencies; she isn’t selling demagoguery. I am certainly not the first, tenth, or ten millionth person to say that Trump’s Make America Great Again campaign has all the sights, sounds, and smells of a would-be dictator. If this were Europe, we would just be a few “Jewish-run banks,” references away from a textbook campaign of fascism.

What would four years of poisoning our national discourse with violent chauvinism, xenophobia, divisiveness, and suspicion do to us as a country? Once we start normalizing molesting women, scapegoating Mexican-Americans, and excluding Muslim-Americans, where does it end? While America’s individualism is a repellent to demagoguery, we are not immune to the danger of delivering the world’s largest pedestal and levers to such an unconscionable man. Trump may not have the foresight to exploit a divided American people toward truly nefarious ends, but there are men surrounding him who would do just that.

Rwanda needed to heal societal cleaves. Instead their leaders pulled them further apart and tore their country to shreds in the process. Emerging from their own ashes, a new set of leaders chose togetherness over division and Rwanda has been ascendant ever since. As we approach an election unrivaled in the profundity of its consequences, I would remind my fellow Americans to learn from Rwanda, leadership matters.